About computers in education, generally

THEME SPECIFIC COMPLAINT

Effect: Computers have not improved education.About learning environments:

Value: Computer experiences are inferior to real ones.

Clarity: The notion is not clear and distinct.The specific complaints we will pursue here are those focussed on the themes of effect, clarity and design. I conclude with some suggestions for future work.[1]

Design: Nobody knows how to make them.

THE LIMITED IMPACT OF COMPUTERS IN EDUCATION

The introduction of microcomputers into the education system has disappointed many people who had hoped their presence would engender reforms leading to education both more congenial to children and more effective than the norm of past generations. There has been no widespread recognition of any such dramatic impact. Why? In a review of Computer Experience and Cognitive Development, Erik DeCorte noted:

"I point to the immediate connection between the book and the current inquiries about using computers with children. Some have claimed that computer experience, and the ability to program in particular, would influence in a positive way the learning and thinking capacities of children. In contradiction to the image produced by the rest of the available research literature (See DeCorte & Verschaffel, 1985), Lawler's study produces positive results concerning the cognitive-effects hypothesis...."

Such negative outcomes as others report, when the result of thoughtful experiments which are executed with care, have the proper function of constraining the enthusiastic claims of the overly optimistic. On the other hand, I am convinced that one reason for the difference of outcomes noted by DeCorte is a consequence of different levels of detail of the studies. Too much evaluative research has the flavor of I/O models: some INPUT should produce some OUTPUT; some INSTRUCTION should produce some OUTCOME. If the true orderliness of human behavior becomes evident only when one looks very carefully at extremely tiny details, most experimental efforts to assess computing's impact will show negative results, unless they examine the PROCESS between input and output, the PERSON between instruction and outcome. Studying the knowledge and functioning of one mind in detail permits a depth of understanding of the student's mind and development normally beyond the reach of research with a broader focus. We need to go beyond evaluative studies of broad claims in order to advance our understanding of human cognition, specifically in respect of the issues of the malleability of the natural mind and of the long-term effects of specific experiences on the lives of individuals: both, for me, are central issues for the science of education.

Comments such as the preceding, though true and valuable, evade rather than answer the question raised by DeCorte's observation. It is the case that early Logo claims looked to widespread results so obvious and striking that corroborating or disambiguating experiments would not be required. No such strong outcome has occurred. Computers, as introduced in schools, have not had so beneficial an impact as their early proponents suggested they might. Let's reflect on this problem.

The Worst Case: The Problem is Not Solvable

Despite widespread research in several paradigms directed to improving children's mathematical competence through using computers, there is a general impression, based on test results, that arithmetic skills have been deteriorating over the past 25 years. One jocular suggestion for reacting to this situation comes from ``The Uses of Education to Enhance Technology" [2]

"It's time to face the facts: all previous efforts at educational reform have been failures. The harder we try, the more innovations we make, the dumber the students get. This is eloquently pointed out by proponents of the 'Back to Basics' movement in numerous riots and book burnings across the country.The solution is clear. It is simply not possible to educate children. If repeated attempts to improve the quality of education only make matters worse, then the obvious way to make matters better is to try to degrade the quality of education. In fact, carrying this argument to its logical conclusion proves that the best educational reform would be to abolish efforts at education altogether. This conclusion is hardly new and has been previously argued by such thinkers as Holt and Illich. But they also foresaw the serious impediments to this scheme. It would abolish the major value of the school system, which is to supply employment and positions of power. . . . But now, with modern technology, we see a way out of this dilemma. The solution is absurdly simple: by placing computers in the schools, we can let the teachers teach the computers and send the children home. . . . Specifically, we envision an educational system in which each child is assigned a personal computer, which goes to school in place of the child. (Incidentally, it should be noted that the cost of such a personal computer is not large. Even at today's prices it is probably not much more than the average family would spend on a catastrophic medical emergency)...."[3]

Those of us who are laughing through our tears can not escape the need for some different way of dealing with the issue. One can try to take a broad view. It is possible to believe that the problem has not been a "local" failure, ascribable in some simple way to faulty research, slow technology transfer, or intractable institutions.

An Explanation: Social Changes are Dominant

The problem may be profound and even could involve deterioration in the learnability of common sense knowledge. Changes in the everyday world can completely overwhelm our hopes to teach children skills we know they will need later. Consider these observations (from Lawler, 1985) as an example of ways in which social forces can radically alter the cognitive impact of domains of common sense knowledge.

Vignette 55Complex technology may also be making the world less comprehensible, but the effects are not uniform. Calculators and modern cash registers which compute change obviate the need for much mental calculation. Contrariwise, it is possible to argue that technology is making access to reading knowledge easier.[4] These observations leave us with more questions than answers, but the questions are addressable and significant ones: to what extent is it possible to learn what one needs to know through everyday experience? how do side effects of decisions by adults constrain or enhance children's ability to learn about the world in natural ways?"Since the beginning of the High School Studies Program, the children and I have come to Logo to use the system from 8 to 10 a.m. The children have become accustomed to mid-morning snacks. The favorite: apple pie and milk. At their young age, Robby and Miriam get money from me, and we talk about how they spend it. A piece of pie costs 59 cents. A half pint of milk is 32 cents. So Miriam told me this morning, and these figures are familiar. As we got her snack, I asked Miriam how much we would have to pay the cashier. After a few miscalculations, she came to a sum of 91 cents and seemed confident it was correct. I congratulated her on a correct sum and asked the cashier to ring up our tab. "92 cents."

"92 cents?" I asked the cashier to explain. She said the pie is 55 cents and milk 30 cents, thus 85 cents and the tax, 7 cents. "See. Look at the table."

I am at a complete loss as to how to explain this to Miriam. Not only is the 8 percent food tax dreadful in itself, but it is rendering incomprehensible a primary domain of arithmetic that children regularly confront -- paying small amounts of money for junk food. Otherwheres, Miriam used "the tax" as a label for the difference between what is a reasonable computation and what you actually have to pay somebody to buy something...."

The observation suggests that a specific governmental policy has, as a side effect, been making the world less sensible and harder to learn about. If, to get accurate results, a child must learn to multiply and round (for computing a percentage tax) before learning to add, he is in BIG trouble. If it does no good to calculate correctly, because results will be adjusted by some authoritatively asserted incomprehensible rule, why should one bother to be over-committed to precision? If addition no longer adds up, what good is arithmetic? If you can't count on number, what can you can you count on? If knowledge is not useful, why bother with it?

An Excuse: The Political Climate has been Adverse

After such observations, it is reasonable to ask how political decisions -- such as support for research -- have influenced the use of computers in education. For many years the federal government, through various agencies, was a major supporter of research into technology for education. The impact of the first Reagan budget -- which proposed to reduce funding for research in science education from $80M to $10M in one year -- led to significant demoralization of that community and deterioration of function within its organizations [5]. The decimation of this community was decidedly unhelpful and may have engendered some of the chaos and superficiality of work evidenced as microcomputers were sold by the private sector to the education community throughout the United States. On the other hand, one must note that the more generous support provided by the French Government's founding of Le Centre Mondial pour l'Informatique et Ressource Humaine had no happier outcome, as noted by Paul Tate in Datamation.

An Excuse: Available Hardware has been Inadequate"The Center intended to use microcomputers to take computing to the people through educational workshops in both the developed and the developing world. Field projects were set up in France and Senegal, and research schemes were introduced covering interactive media, systems architecture, AI, user interfaces, and medical applications. It was to be an international research center independent of all commercial, political, and national interests. Naturally, it failed. Nothing is that independent, especially an organization backed by a socialist government and staffed by highly individualistic industry visionaries from around the world. Besides, altruism has a credibility problem in an industry that thrives on intense commercial competition. By the end of the Center's first year, Papert had quit, so had American experts Nicholas Negroponte and Bob Lawler. It had become a battlefield, scarred by clashes of management style, personality, and political conviction. It never really recovered. The new French government has done the Center a favor in closing it down. But somewhere in that mess was an admirable attempt to take high technology, quickly and effectively, along the inevitable path into the hands of the public. The Center had hoped to do that in different countries. . . . The Center is unlikely to be missed by many. Yet, for all its problems, it made a brave attempt to prepare for some of the technical and market realities of the next few years. We regret that such a noble venture met with such an ignoble end." [6]

There is no question that the introduction of computers in education was a financial success -- for some few companies -- but the record with respect to product engineering and the advancement of social goals is one of nearly consistent failure. Consider, as an example, this brief review of the development of Logo-capable microcomputers for education:

An Explanation: The Medium Has No Consumable Content

The disappointing impact of computers on education may be partly explained by the lack of content addressable with the technology. Consider, in contrast, the video cassette recorder. VCR's have reached a "take-off" point and now are present in over 30 percent of American homes. A key element in the success of VCR technology -- not only in the market but also in user satisfaction with it -- is the existence of a massive stock of material which the VCR brought to a new level of accessibility. As a "follow-on" technology, VCR's reproduce for resale the production of 70 years of film and TV with marginal conversion costs.

What existing material do micros have accessible? Ideas? Yes, but they must be recoded for each new system unless microcoded emulation of predecessor machines becomes common. More to the point, existing larger systems and minicomputers typically have different purposes than did micros purchased for education. To offset this limitation, conversational programming languages suggested the possibility of extensive programming by end-users. What precisely that meant and what has evolved from that hope is a theme discussed in the various texts under the headings of Education and Computing.

Publication notes:

Text notes:

|  |

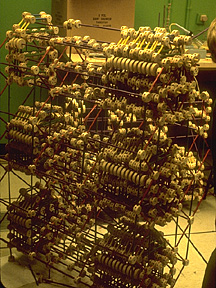

Technology is just stuff. What's important is thinking about one's experience. One ambition of the Logo project was to make stuff that young people would find worth thinking about. You see Rob on the left sitting like Rodin's Thinker in the midst of Tinker Toys. What Has He Got To Think About ? The device on the right is a computer, made out of wooden Tinker Toys, by some of the marvelous young people who hung around the lab. Margaret Minsky, Danny Hillis, Gary Drescher, Ed Hardebeck, Brian Silverman, Steve Haines, Pat Soblavero, Leigh Klotz, and many others whose names escape me now. They were the real learning environment; with the founders and staff of the Logo lab, they all saw computing as a medium for expression and thought-full play.