I have worked in the computer industry for sixteen years, and when my children

were born I became interested in the potential impact of early computer

experiences on children's learning. Several years ago, in collaboration

with a computer language project at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology,

I began an intensive study of how daily access to a computer influenced

the way my two older children--then aged six and eight--learned the basics

of arithmetic. By the time their younger sister Peggy turned three, a microcomputer

had become standard equipment in our household, and I began to develop several

programs to give Peggy access to the machine. Playing with these programs

in her own way and on her own initiative over the following months, Peggy

began to do something that looks very much like the beginnings of reading

and writing.

What is it really like to bring a microcomputer in your home and let your three-year-old play with it? The answer depends on who you are, your knowledge and values. The computer entered my home and my family life because it is a part of my work. It was my pleasure to write some simple programs for my daughter's entertainment and edification. My interests in children and computers led me to gather a great deal of information about what Peggy knew before her first encounter with the computer and afterwards. Between her ages of three years three months and three years ten months, Peggy began to read and write. The following sketch of how this happened is based on my own observation of only one child's learning; it is fair to say, however, that I have an enormous amount of detailed information about what this particular child knew and how that knowledge changed over a long period of time. I believe this sketch will be of general interest because Peggy's story provides some advance information about how computer experience may affect our children.

In the USA children typically learn to read around the age of six. Most

learn to read at school. A few teach themselves to read earlier. Peggy,

at the age of three, even living in a bookish family, did not know how to

read in any substantial sense before her computer experience. Her knowledge

of letters at three years, three months was quite specific and limited.

She recognized only a few letters as distinct symbols with any meaning.

For example, she knew that "P" was the first letter of her name.

She also recognized "G" as the "mummy letter" because

her mother's name is Gretchen.

What was Peggy's knowledge of spelling like? One incident gave me some inkling.

My oldest daughter was learning a bit of French: one day Peggy claimed that

she knew how to "spell French" and continued, "un, deux,

trois, quatre, cinq. " At another time her spelling of "French"

was "woof boogle jig." Peggy saw the process of spelling as decomposing

a meaningful word into a string of essentially meaningless symbols and had

not yet learned any of the standard spellings of words.

Peggy's ability and willingness to identify a string of symbols as a particular

word came from a very specific beginning. After receiving a gift book from

her older sister (who then wrote Peggy Lawler on the flyleaf), Peggy interpreted

all small clusters of alphabetic symbols as "Peggy Lawler. " At

a later point in time, as a consequence of being often read to, she became

able to recognize a single, two letter word, "by", which appeared

on the title page of every book we read to her. There is no reason to believe

she had any idea of what "by" might mean in that context. Her

knowledge of reading as a process for interpreting graphic material is best

seen in her common observation that she read Pictures and I read Words.

From her remark. we can infer she would expect to do the same with words. Not a bad assumption,

but completely empty of any information about how written words signify

as they do.

Contrast now her knowledge seven months later. Her knowledge of letters

is essentially complete, in that she discriminates the 26 letters of the

alphabet and can name them. Her knowledge of words, in the sense of interpreting

them one at a time, is significantly greater. She reads more than 20 words,

most with complete dependability. But unlike children who have learned to

read and write by conventional means, she sees the spelling of words as

stepwise directions for keying a name into the computer. Although her general

idea of what book reading is may not have changed, she has a different and

powerful idea of what reading single words means that derives directly from

her experience with my computer programs. Peggy's introduction to computers

did not relate directly to "reading" in terms of content, but

her desire to control the machine led her into keying on the computer her

first "written" word. Having helped load programs by pushing buttons

on a cassette tape recorder, one day on her own Peggy typed "LO"

on the terminal then came seeking direction as to what letter came next.

A few days later, she typed the "load" command while the rest

of the family was busy elsewhere.

I call the computer environments created by the programs I have written

"microworlds", following the terminology used by Seymour Papert,

the man chiefly responsible for the development of the "LOGO"

computer language, in his book Mindstorms. The initial microworlds were one for moving coloured blocks around on the

video display screen and another (made for her older sister but taken over

by Peggy) which created designs by moving a coloured cursor. While her sister

used this drawing program to make designs, Peggy's first drawing was a large

box--which she immediately converted into a letter "P" by adding

the stem. Letters intrigued Peggy. They were a source of power she didn't

understand.

A few days later, Peggy keyed the letter "A" and explained to

me that "A is for apple. " Her comment suggested away we could--on

the computer--make a new kind of prereaders' ABC book. A child's book of

ABC's typically offers a collection of engaging pictures displayed in alphabetic

order with a large, printed letter associated with each picture. The child

looks at the pictures and is informed "A is for apple. " The relationship

of letters to pictures is exactly the opposite in the ABC microworld. The

letter is the "key" for accessing the picture. That is, keying

the letter "D" produces a picture of a dog. Instead of responding

to a statement such as "See the doggie. D is for dog, " Peggy

was able to try any letter on the keyboard, first, to see what it got her,

and later, if the picture interested her, to inquire what was the letter's

name. She was in control of her own learning. She could learn WHAT she wanted,

WHEN she wanted to, and could ask for advice or information when SHE decided

she WANTED it. The ABC microworld was tailor-made for Peggy. The shapes

were selected and created on the computer by Peggy's older sister and brother,

aged ten and twelve. As a consequence of playing with the ABC microworld--and

with another to which we now turn--Peggy developed a stable and congenial

familiarity with the letters of the alphabet.

These microworlds were created using Logo, an easily comprehensible computer

language which permits you to assign meaning to any string of letters by

writing simple procedures. Logo's procedure definition was especially valuable

in customizing the BEACH world. When Peggy first used BEACH, she was unhappy

with the speed of the objects and asked, "How can I make them zoom,

Daddy?" Nothing was easier than to create a new Logo word, ZOOM, which

set the velocity of the object with a single primitive command. In a further

instance, Peggy's older sister made a horse-and-rider design and wrote a

PONY procedure to create an object with a horse-and-rider design and set

it in motion. After watching her sister edit that shape design, Peggy imitated

the specific commands to create her own new shape. (She could not well control

the design and ended with a collection of perpendicular lines. Asked what

it was, she first replied "A pony, "then later, "Something

important. ") It is very likely that primary grade children could create

their own designs and would copy and alter procedures to expand or personalize

the vocabulary of BEACH-like microworlds.

As a direct consequence of playing with the BEACH world, Peggy learned to

"read" approximately twenty words. Initially, she keyed names

and commands, copying them letter by letter from a set of cards. Soon, her

favourite words were keyed from memory. Less familiar words she could locate

by searching through the pile of cards. When her mood was exploratory, she

would try unfamiliar words if she encountered them by chance. Now, when

shown those words--on the original cards or printed otherwheres--she recognizes

the pattern of letters and associates it with the appropriate vocal expression.

Further, the words are meaningful to her. She knows what they represent,

either objects or actions.

In the past, words for reading have always been an alphabetic symbol for an idea to be evoked in the mind. For Peggy, words are that but something else as well--a set of directions for specifying how to key a computer command. What is strikingly different in this new word-concept, as contrasted with quasi-phonetic decoding, is that the child and computer together decode a letter string from a printed word to a procedure which the computer executes and whose significance the child can appreciate. Finally, because the computer can interpret specific words the child does not yet know, she can learn from the computer through her self directed explorations and experiments. What might the words of this world mean ?

Learning to read from print is necessarily a passive process for the child.

Words on the page stand for other people's meanings. Until children start

to write, they can't use written words for their own purposes. Microcomputers

put reading and writing together from the start. A word that Peggy can read

is also one she can use to produce on the computer effects that interest

her. For Peggy, learning the alphabetic language has become more like every

infant's learning of the vocal language. Speaking is powerful for the infant,

even for one who commands but a few words, when a responsive person listens.

Likewise, the production of alphabetic symbols--even one letter and one

word at a time--can become powerful for the young child when computer microworlds

provide a patient, responsive intelligence to interpret them.

Since speech is natural to man in all the various cultures of our world,

it is reasonable to ask whether the most general and powerful elements in

Peggy's experience with writing can be adapted for use in cultures other

than the one to which she is native. If computer technology could make learning

to read and write more like learning to speak and understand, it would be

capable of changing profoundly the intellectual character of the world in

which we all live.

The essential power available through the Logo computer language is that

a word, any string of symbols, can be given a function. For example, the

word "SUN" can cause the execution of a computer procedure which

produces a graphic image representing the sun. Because both the spelling

of a word and the meaning given to it are assigned through writing a procedure,

the words of computer microworlds are independent of the "natural"

language of the programmer. For example, the same procedure which creates

the "SUN" could be given the name "SOLEIL" (French)

or "JANT"(Wolof). Although computer words may be language independent,

anything made for use by people is culturally bound. Only people who share

the same cultural experience scan know which objects and actions within

a culture will be congenial to the children and will relate to the kind

of homely experience which is close to their hearts and will continue to

engage them in learning and loving learning.

The people who should determine what computer experiences are offered to

children should be the children themselves, their parents or their teachers--or

others who are close to the children and share their experiences--hopefully,

sensitive, caring instructors with a progressive commitment to what is best

for the children they love. Computers and their languages should be accessible

to such people, easy for them to use as a casual, creative medium. If they

are not so, the children of the world will not be properly served.

One lucky day, Peggy and I showed her BEACH microworld to two such men,

Mamadou Niang and Moussa Gning. These gentlemen, Senegalese teachers who

had come the New York Logo Center for an introduction to computers and the

Logo programming language, were engaged by these microworlds I had made

for my daughter. They told me that the Senegalese people are much concerned

with the issue of literacy and hoped that computers could make learning

the written word more congenial to the children of their nation. Their colleague

and technical adviser, Mme Sylla Fatimata, later explained the importance

computers could have to their children in this way.

The children of Senegal typically live in a personal, warm family setting

until they are of school age. At home, they live and grow in the culture

of their traditional languages, such as Wolof. At school age, they go off

to a cold and impersonal place where all the language and all the lessons

are French. Some children survive and thrive there, but many are terrified

and refuse to learn. For them, learning in school means alienation from

the people they love, and they reject that alienation even though they are

encouraged to adopt it.

French is the dominant language through which the Senegalese deal with the

exterior world. It is the language of opportunity within the government

and commerce. Further, it is the language which has dominated the schools

and continues to do so. The Senegalese intend to protect and advance their

traditional languages by turning the tide of modern technology to their

own use, specifically by developing literacy in Wolof among their children.

Although Wolof has been written--in an extended Roman alphabet--for more

than a hundred years, only during the last decade has the transcription

of the language become standardized throughout the country. Consequently,

and ironically, many learned people of their land, literate in French and

even Arabic, are illiterate in their traditional language, the language

they use in their homes and in conversation with their African colleagues

at work.

Wanting to change this situation, the Senegalese believe they might better

create programs for computer use in Wolof than in French or in the language

of whoever makes the machines, and they have good reasons. Because there

exists now no rigid "curriculum" for computer education in French,

and because they have not invested years in teacher training in French language

computer instruction, they imagine correctly that this new technology has

a revolutionary potential which can be used to support their traditional

language and culture if they but seize the opportunity.

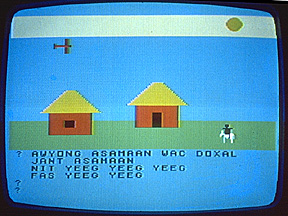

With others of the Senegal Microcomputer Project, Mamadou Niang and Moussa

Gning came to extend their introduction to Logo in Paris--at the World Center

for Computation and Human Development. Because there is no better way to

learn how to use a computer language than to use it for some significant

purpose, I offered Mamadou this challenge, "You imagine some such microworld

for the children of Senegal, and I will help you make it; let's work together

to make something your young students will love. "Mamadou noted that,

of course, there are beaches in Senegal and the great city of Dakar, but

that since an objective of their work was to appeal to all the children

of Senegal, it would be more appropriate to think of images of the countryside.

He proposed a village backdrop, with some small buildings and a well. To

enliven such a scene, one would need people and the animals of the country

life, perhaps a cat, horses, cows and so on. We agreed to make only a few

objects, and thereby leave for the children the pleasure of creation; we

would let them decide what they wanted in their world--and provide the tools

for them to make it.

Since we come from cultures so much apart, it is appropriate to comment

on our way of working together. We labored to share ideas. Our working tongue,

our lingua franca, was French; after all, in Paris tout le monde

parle français. . Mamadou and Moussa spoke French much better

than I did. I was grateful that they would tolerate my poor French so that

we could work together. The computer we used was an English language Logo

computer. When they succeeded in helping me understand their objectives,

I would propose and demonstrate programming capabilities and techniques

to embody what Mamadou wanted in the microworld. In a kind of "pidgin"

language, French, English, computerese, they began to program with my guidance

a little scene, some designs of objects to fit in that scene, and some computer

procedures to control their appearance and actions.

When we had created a scene with a number of French language procedure names--when

we had the conceptual objects of this world more or less under control--we

began to discuss using Wolof. This is where Moussa played a most significant

role. As the leading primary-grade pedagogue for Wolof instruction in Senegal,

he was able with confidence to assign definitive spellings to the procedure

names we used to create and manipulate the objects of our village microworld.

(Sometimes this involved consultation with the others of the Senegalese

delegation, including the linguist, Pathe Diagne. )

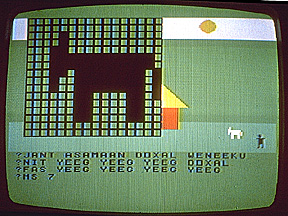

Because the Logo language permits any string of "keyable" symbols

to be the name of a procedure, we were able to convert French-named procedures

such as"SOLEIL" and "MARCHE" to their Wolof equivalents,

"JANT" and "DOXAL" (the "X" is pronounced

as in Spanish). Thus we arrived at the assembly of procedures and designs

capable of producing the village microworld, "XEW". (The sound

of the name "XEW", meaning "scene", begins with the

Spanish "X" and rhymes with the English "HOW". )

If the village microworld seems bare and crude, there is good reason. It

was not made to impress programmers or civil servants. It is less a product

than a project with a few examples of what is possible. This world is one

to be created by the children of Senegal. Why should I tell them what they

want? Why should even their teachers tell them what creatures and people

to put in the worlds of their imaginations?

It was Mamadou who best expressed the right way of viewing the village microworld. When I said that the design of "FAS" was incredible, looked ever so little like a horse, he replied "I'm sure the children will make a better one. "

Publication notes:

Text notes:

|

|

On closing of Le Centre Mondial ten years after its founding, the building shown here passed to other commercial uses.